During our March expedition, we retrieved four of of the coral settlement tiles that we planted on the reef last year to look for the settlement of coral babies. Two came from the nearshore reef called Harati and the other two from one of the offshore reefs called Kisci’s Garden. I moved the microscope from Tela Marine’s Aquarium to beautiful Los Olingos Lodge, where I was staying, and turned the meeting hall into a science lab.

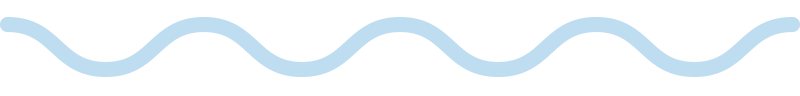

Looking through the tiles is micro-diving into a world of astonishing life. Adjectives catapult through your mind trying to define the unfamiliar world that becomes seen for a moment. And they can’t do it justice The sheer variety of life on six square inches is one of the most awe-inspiring things I know. One night, my friend Missy and I stayed up until midnight exploring just one single tile.

Looking through the tiles is micro-diving into a world of astonishing life. Adjectives catapult through your mind trying to define the unfamiliar world that becomes seen for a moment. And they can’t do it justice The sheer variety of life on six square inches is one of the most awe-inspiring things I know. One night, my friend Missy and I stayed up until midnight exploring just one single tile.

Look closely to see a cool crustacean, clear as glass.

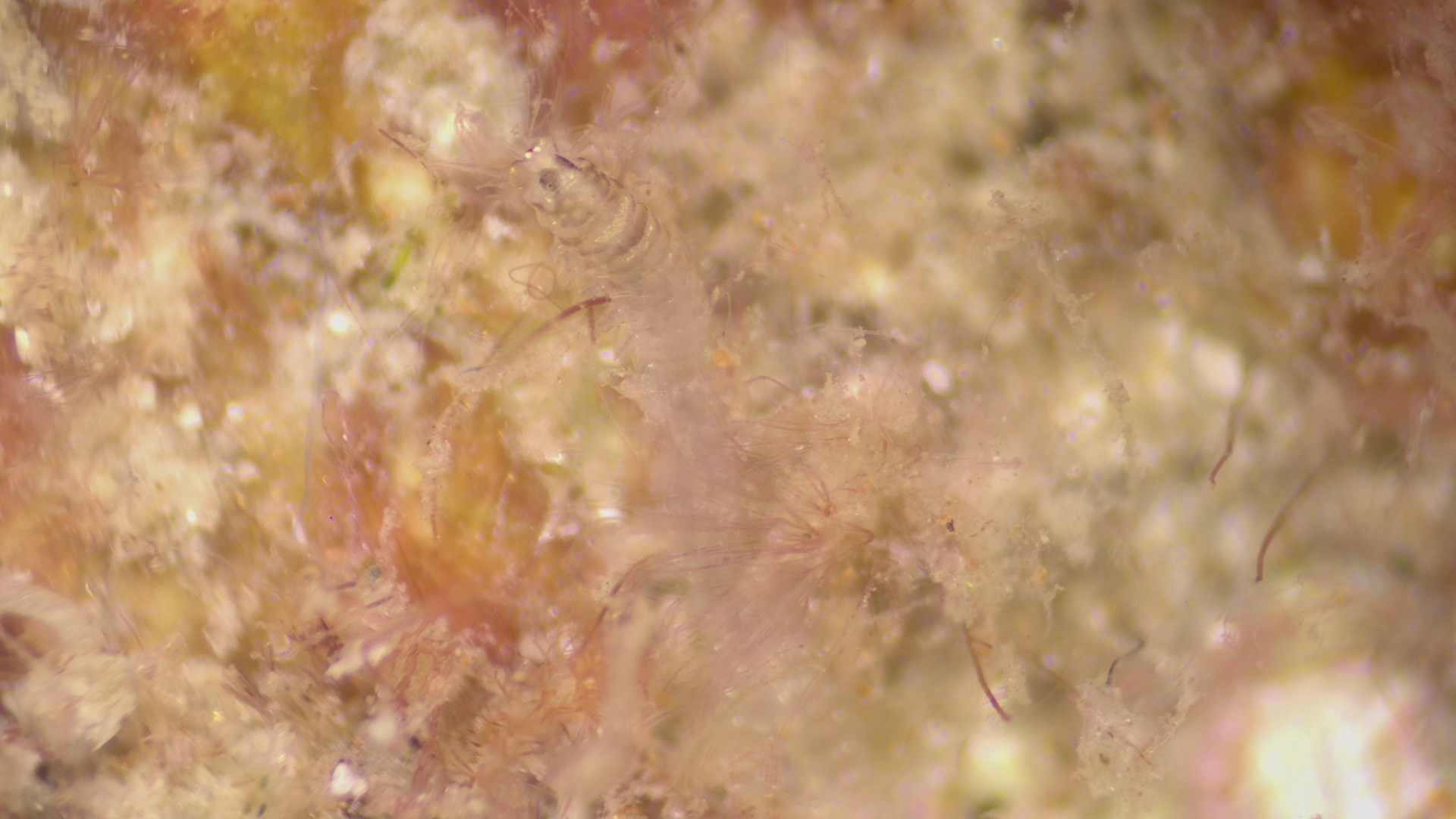

The elegant filigree of a sponge

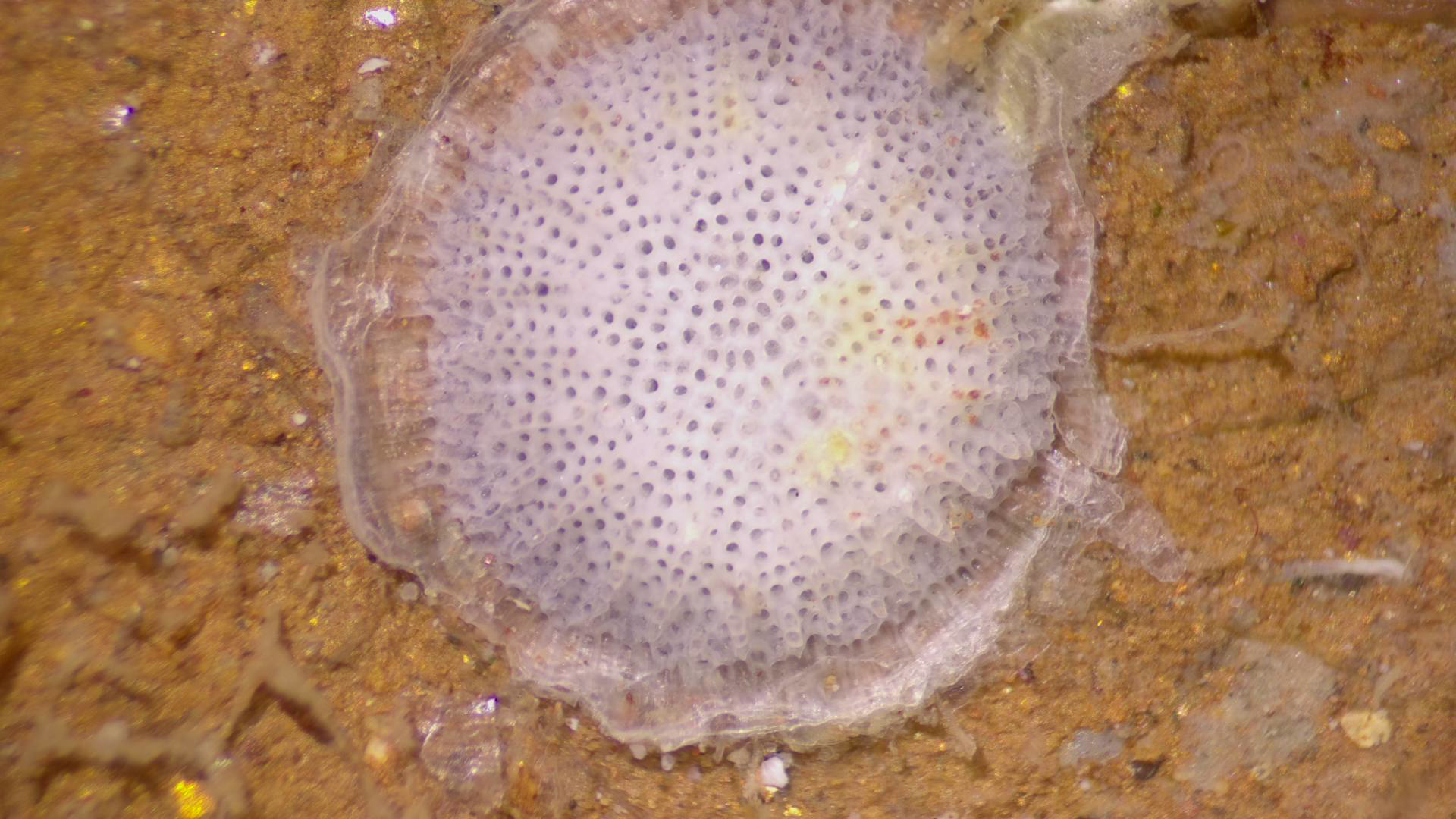

We don’t know what these circular things are – a mystery! – but we see them all the time.

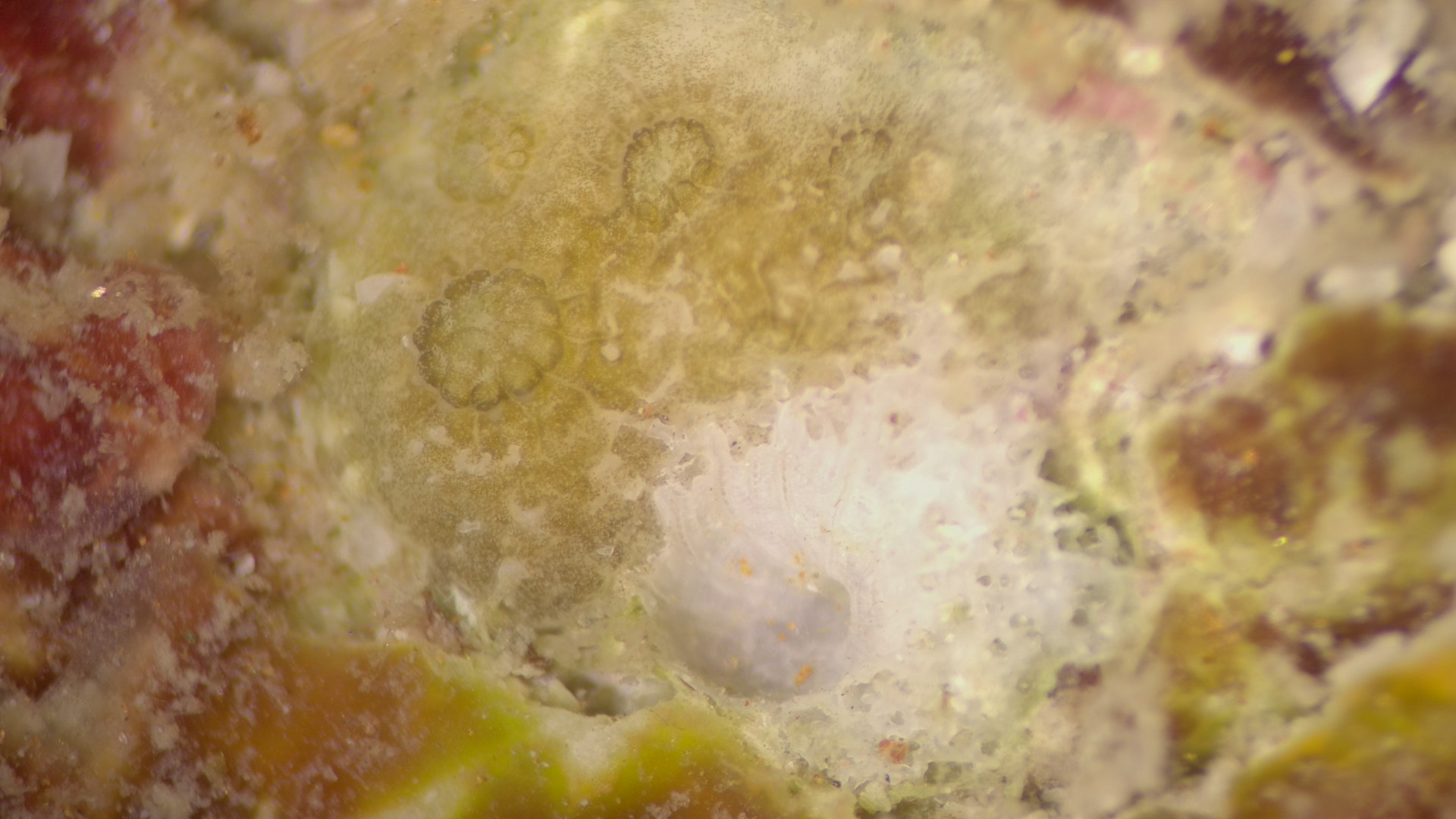

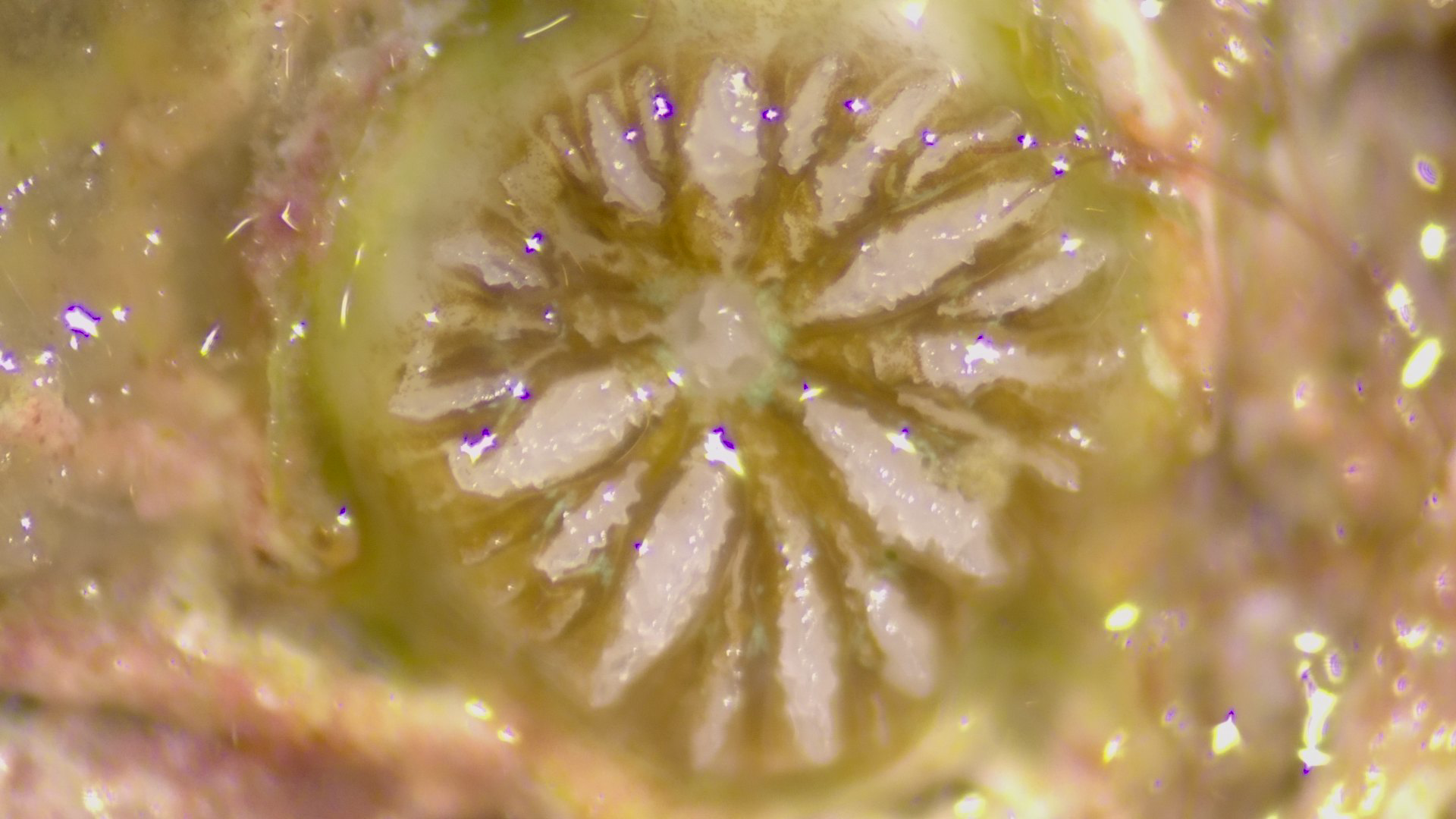

Although we discovered an amazing menagerie, we didn’t a coral that first night of looking. But the next morning, I fired up the microscope before breakfast and pulled out a second tile, this one from Kiscis Garden. I was engrossed again in the weird and wonderful world of the micro reef when suddenly, I came across not just a single polyp, like we found last year, but an entire colony.

It was like coming upon a little field of daisies. I saw one circle first, and then the petal-like tentacles. Then I noticed a second polyp, and a third and a fourth. And finally seven. I touched one slightly with the tip of a probe. It pulled itself into its skeleton. It’s the weirdest thing when you are looking for corals in a microscope. You see so much life that you begin to second guess whether you’ll recognize a coral. But then when you see one, you know it with great certainty.

A breakfast, it hit me that there was no way I’d have time to search the rest of the tiles. It was our last day in Tela and just one and a half tiles had taken one and a half days of micro-diving exploration. There was only one thing to do. I changed my flight so I could spend on last day looking through the tiles.

Missyasked, “Are you going to spend the whole day looking at tiles?”

“Yes,” I answered, and I could see the jealously behind her smile as she debated whether or not to join me. But she had responsibilities in the US, and I know she’ll be back to look at more tiles with me. She’s hooked too.

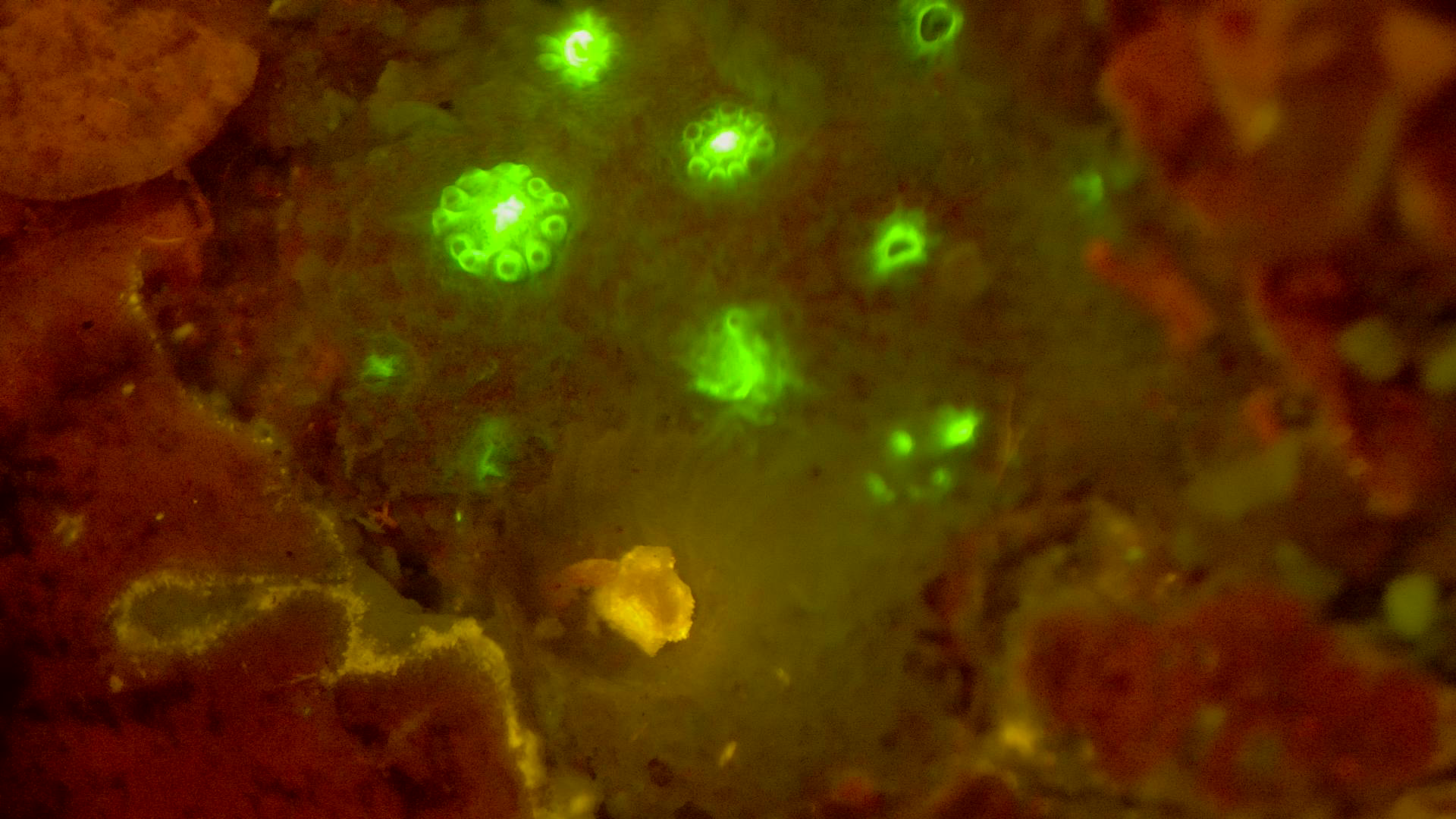

Back to the Tela Marine Aquarium, I remembered about green fluorescent protein. Corals, and most (if not all – I’m not sure) cnidarians, which include jellyfish, sea anemones, and hydrozoans, produce this special protein, GFP. No one really knows what it’s purpose is, but there’s speculation it might be used to prevent damage to cells One study I just found suggests GFP is a signal to attract coral symbionts.

What GFP does that’s very helpful to science is absorb violet-blue light, change its wavelength, and re-emit it as green-yellow light. So if you shine a UV light on a coral, and put a green-yellow filter on your microscope so you can only see the wavelengths the that the GFP emits, you should see your coral glowing.

At that point, a visiting coral scientist from WCS Mozambique named Erwan Sola had stopped by the room where I’d set up the microscope. He’d worked on coral settlement tiles for his Ph.D. and was just as entranced by the baby colony as I was. We changed the setup of the microscope to see the GFP and turned out the overhead lights.

It was like the solar system lit up in a pop! Erwan and I both shouted in awe. The little polyps looked like UFOs.

After we took plenty of photos, we turned to the other tiles. Erwan had to leave and I was on my own in the hunt. Time was running short. Just before the end of the day, Antal stopped by to check on my progress. I hadn’t found any more babies, I said. But then, almost as the words left my mouth, on the side of one of the tiles from Harati, I found one more. A sweet little snowflake.

After we took plenty of photos, we turned to the other tiles. Erwan had to leave and I was on my own in the hunt. Time was running short. Just before the end of the day, Antal stopped by to check on my progress. I hadn’t found any more babies, I said. But then, almost as the words left my mouth, on the side of one of the tiles from Harati, I found one more. A sweet little snowflake.

I left the tiles in the capable hands of Senyacen Ramirez, Tela Marine’s biologist. She’s going to bleach them and take another look to see if there are more signs of coral life on the tiles. I’m certain I missed many settlers. Last year we discovered about four times more corals after we bleached the tiles, which clears away all the algal overgrowth leaving coral skeletons behind.

The thing we can say, again, is that Tela’s reefs are still producing babies, both inshore and offshore. Half the tiles I pulled had babies on them. Which is great and unusual news, and a big part of what makes Tela so special. Many coral reefs in the Caribbean are no longer reproductive. And there are still 46 tiles out there on the reef waiting for micro-diving exploration!