We don’t know! But we hope to find out.

During the hottest months of the year, a few days after the full moon at an auspicious moment after the sun sets, coral release their gametes into the sea. While the exact timing is well-known to each and every coral species–their very existence depends on it after all–the whole event is mysterious to us human observers.

I’ve had the amazing experience of diving during a coral spawn it feels like you’re in the middle of an upside down blizzard. But if those eggs aren’t fertilized, and the larvae produced aren’t viable, then the future of the reefs are in jeopardy. Such conditions have been documented in other parts of the Caribbean leading to what are called zombie reefs.

In Tela, no one has ever documented the coral spawn. But it’s critical that we try to find out more about it. If Tela is a seed bank for other parts of the Caribbean, a first step is to understand where and when those seeds are produced. That’s why ACT launched our first alt ac (aka: alternative academics) scientific expedition a few days after the full moon this October. Our aim was to provide coral larvae that might have formed from this year’s spawn cradles on which to grow.

Where do coral babies like to settle? According to other researchers—and there’s been a significant amount of work on this—coral larvae like to cuddle up in semi-light on hard surfaces that have a coating of bacteria and coralline algae.

About a month before we arrived, TelaMarine’s biologist Senjacen Ramirez placed a hundred terracotta tiles in a big bucket and then submerged the entire thing near the dock where TelaMarine’s dive shop is located. The idea was for the tiles to become coated in the oceanic microorganisms that larvae seek as a sign for settling. Once we arrived in Tela, we’d drill holes through them and then attach them to the reef.

Up in Texas, I conferred with Florida Tech’s Robert van Woesik, who has worked on similar studies in the Florida Keys for details. That led to repeated trips to the hardware store for stainless steel screws, nuts, bolts, clips, wrenches, zip ties, drill bits, and underwater cement. Misha Matz’s lab at UT graciously donated cow ear tags to mark the tiles, amazingly small temperature loggers that look like green bottle tops, and water bottles to use to sample the water quality.

That’s when I learned of the idea of a shiskabob from Misha’s student Kristina Black. More tiles, less drilling.

Still, I was worried about securing screws onto the reef with a hand drill that I’d ordered. I called Tiff who wisely pointed out, “Without a way to drill we won’t be able to do anything else.” I pulled the trigger and bought the queen of all underwater drills: the Nemo V2 electric drill. It was the best decision we made.

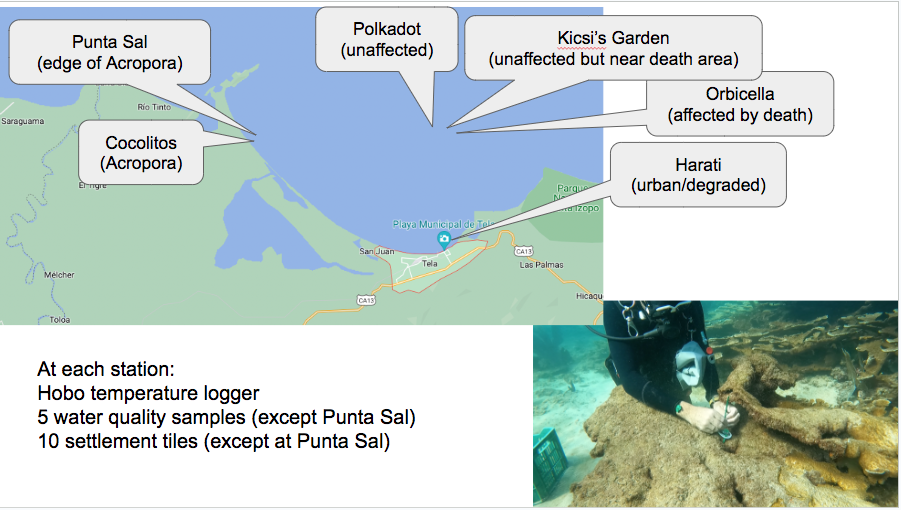

Once we to Tela, we planned our approach. We would attempt to install ten tiles in four stations along with securing the temperature loggers and taking water quality samples. One station would be near shore where we know that the town’s runoff has compromised the reef, a dive site called Harati. One would be in the elkhorn thickets near Cocolitos, a place rich with a critically endangered species called Acropora palmata. (We also droppped an extra temperature logger nearby at Punta Sal.) A third station would be in an offshore reef that was healthy called Polkadot, and a final station in an offshore reef that had been affected by a strange death earlier in the year called Orbicella for the house-sized corals that live there. (More on that in another blog.)

Underwater, we learned a lot really fast. Drilling into the reef was not as hard as anticipated because the Nemo V2 is the bomb! Shiskabobs were unstable the way we’d envisioned them. Tiles needed to be carried down in bags, not crates, which were bulky and hard to manage. It was best to set up a division of labor: driller, tile placer, tagger, photographer. While it took us probably two hours to put in ten tiles at our first station, we were down to half an hour at our last station. We got so good, we added an extra station in a healthy offshore reef, Kiscis’s Garden, securing a total of fifty coral cribs in the bay.

And I think about them every day. I marvel at the task of a larva, which like a grain of rice swimming with its tiny cilia in that massive sea. Somehow it has to avoid predators, find its way to a reef, find the right spot on the reef, crawl to its forever home, plant itself in a place where it will be invisible to predators long enough to grow a skeleton while still managing to bask in enough light to woo algae to live in its tissues. It’s so much to accomplish for a little tyke. And yet, the vast, rich reefs of our planet are evidence of immense numbers of past successes. We’ll return in April to–fingers-crossed!–take stock of Tela’s newest, smallest victories.