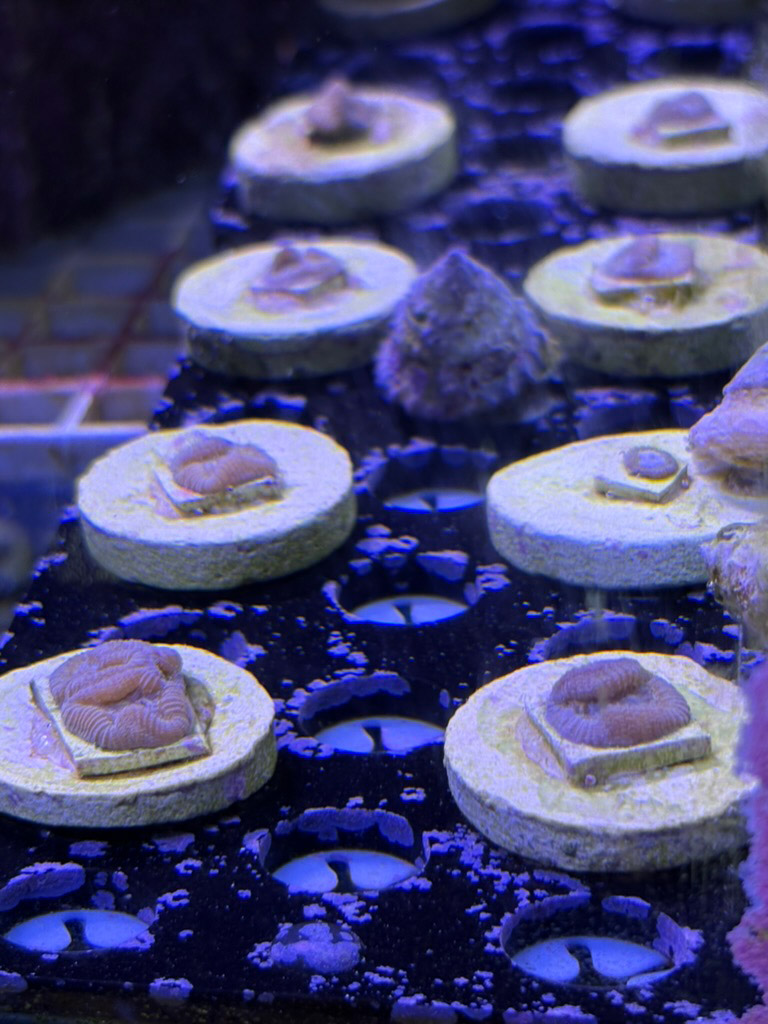

Our efforts to raise funds through Music for the Ocean and through the Stanley Creators Grant are already paying off. We have recently taken delivery of the tanks for the corals, have hired a local Honduran company to help build out the life support systems, and are working with an architect to develop the plans for the facility’s structures.

This critical facility will not only secure the genetic diversity of Tela’s corals, it will provide the space for scientists to come to Tela to work and train Honduran aquarists in coral husbandry.

In collaboration with Dr. Andrew Baker, thirteen of Tela’s rare elkhorn corals were transported to Florida, along with a dozen other coral of five different species. This was our first world’s first.

Soon after, Tela’s elkhorns spawned and were crossed with Florida-born elkhorns, resulting in Flondurans. Andrew received permission, for the first time in the world, for sixty of these non-native corals to be returned to the sea. This was our second world’s first.

The Flondurans continue to flourish off Key Biscayne, and continue to be monitored closely. But this has opened to door to discussions of other international collaborations that might just change the future of coral reefs.

Tela is located in a place where plantations have been leaking fertilizer into the ocean longer than almost anywhere else in the Caribbean. We think this might have created conditions that pushed corals to develop adaptations to today’s more polluted seas.

Coral skeletons are a record of environmental conditions, similar to tree rings. Working with MPI’s Jonathan Jung, we have collected cores of coral skeletons (the coral recover quickly) going back many decades. This analysis will provide critical context for understanding why Tela’s corals are so resilient.

One of the reasons that scientists continue to hold out hope for corals, even in challenging times, is that they have a lot of evolutionary tricks up their tentacles. Among them: they hybridize easily. That means there’s often more genetic diversity on a reef than there appears to be. That can result in behaviors and adaptations that might be advantageous in warmer, more polluted seas.

Daisy Flores and Alexa Huzar from UT as well as Bibi Renssen from Scripps Institute of Oceanography joined us in Tela to take a closer look at Tela’s reefs’ genetics and metabolomics. They will not only look for cryptic species among Tela’s coral community, but also evaluate the types of metabolism the corals rely on to survive.